The Man with a Hole in His Stomach

When I was a child, we had the usual family myths. These included don't drink milk after eating an orange, it will curdle, don’t sit on the cold step or you’ll get king cough (I never found out what that is), and boiled onions in milk stop you from catching a cold (it may just keep people away from you, so you don't catch anything). There was also an obsession with getting enough fibre, which isn't necessarily a bad thing, but it's extreme when you get interrogated about it when visiting your nana. Are any of these ideas true? How can we find out?

Part of the science you study in school is how your body works. A vital organ system is your digestive system, not that the rest are unimportant. We don't usually think about what happens after we swallow our tea unless something goes wrong, but an awful lot is happening that we can't see (believe me, that’s a good thing).

The breaking down of large, insoluble molecules into small, soluble molecules using enzymes.

Enzymes are chemicals that break large molecules into small ones, like scissors.

Molecules are the smallest part of the chemicals in your food.

Your digestive system is a factory that processes your food, takes out the good bits and gets rid of the waste. During this, your food is chopped up, dissolved, mixed with chemicals, and munched on by bacteria. Most of your faeces (poo) are bacteria. Most of the rest of you are bacteria too.

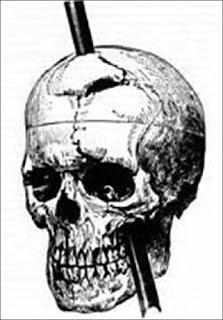

In 1822 Alexis was working at a fur outpost in Canada. He was severely injured when he was accidentally shot with a musket. It was a nasty wound, and the doctor that helped him, Doctor William Beaumont (I need you to boo when I mention him), didn't think he would survive. He did get better, but his wound didn't heal properly, and he ended up with a hole in his side leading to his stomach

.

The hole didn't stop Alexis from working or living his life. Nor did it hurt, but Doctor Beaumont wanted to conduct some experiments. He tricked Alexis into working for him and forced him to participate in the experiments. He carried out over 200 experiments on Alexis over ten years, even though it was obviously uncomfortable.

Dr Beaumont would take pieces of food and dangle them on pieces of string through the hole. He would then pull the food out to see what had happened.

What did Dr Beaumont discover from all of this?

- your stomach contains hydrochloric acid.

- the acid is secreted (let out) by the stomach lining.

- meat is broken down quicker than vegetables.

Alexis did eventually leave the doctor, moving away and refusing all the doctor's pleas to let him do more experiments. He lived until he was 78, dying in Quebec in 1880. He had lived with the hole for over 50 years.

Scientists know now that your food is mixed with gastric juices in your stomach. The hydrochloric acid dissolves your food, your stomach moves around and combines everything (that's what the gurgling is), and enzymes digest proteins, which explains Doctor Beaumont’s meat results. The mixing and dissolving occur for about 2 hours until the mixture empties into your small intestine.

Now we move on to the large intestine, where water is absorbed. What's left now is fibre, bacteria and other bits of food that can't be digested. This waste sits in your rectum until you are ready to get rid of it when it's pushed out through a hole called the anus.

Today doctors use small cameras on devices called endoscopes to investigate the inside of patients. They can see inside a patient’s stomach or intestines using the already available openings. Scientists are always looking for better ways to take images of patients’ inside. This is called medical imaging, which helps doctors discover what’s wrong with a person. Perhaps you can help develop a new method.

.gif)

Comments

Post a Comment